For Beer, Wine and Spirits, It's 1781 All Over Again

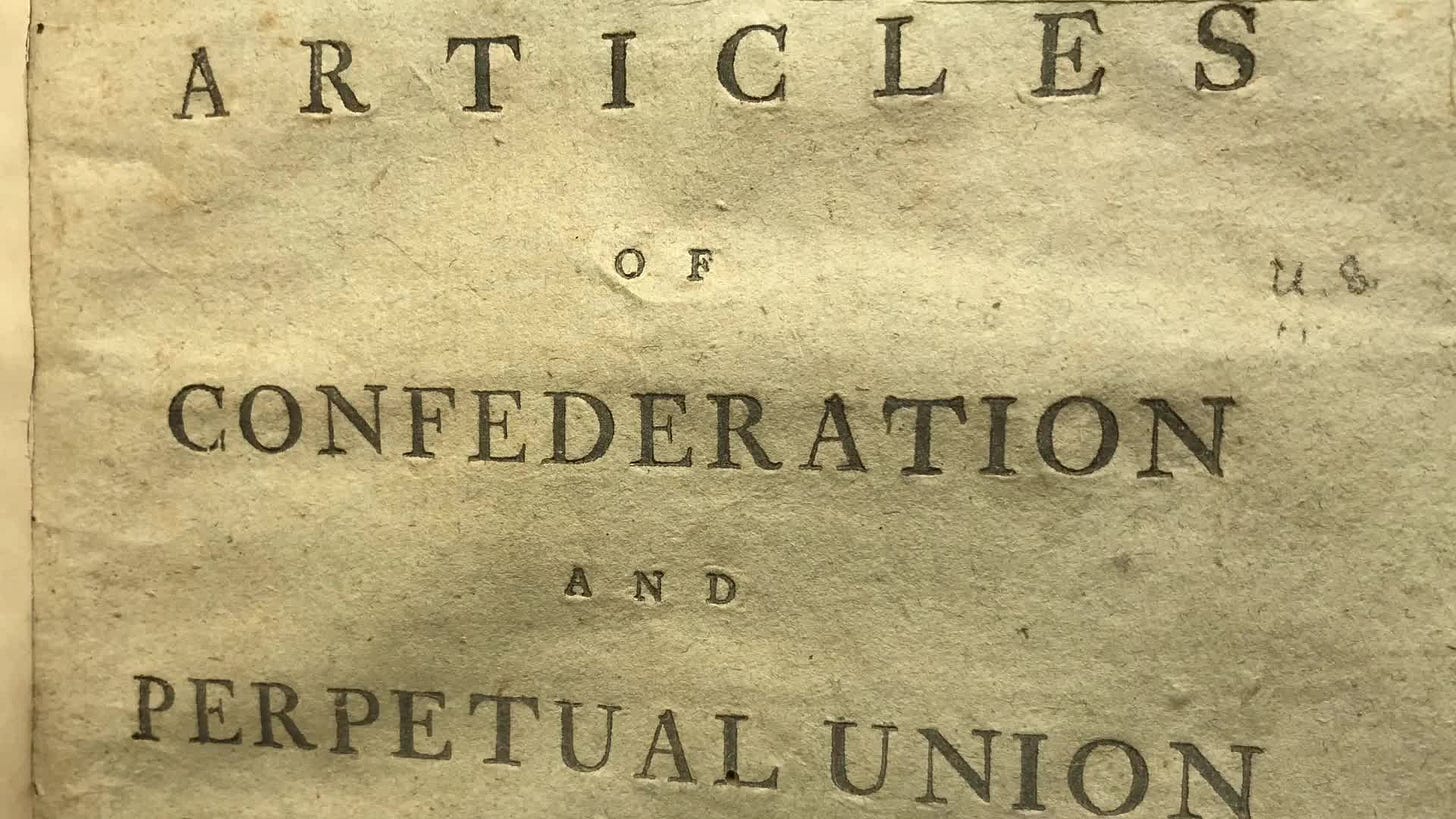

Constitution Day reminds us that state Lawmakers will choose the Articles of Confederation over the Constitution every time

The problem with state-level politics is that lawmakers can’t help themselves. The nature of local politics drives them to help those who help them get elected. And when no one outside the state can vote for lawmakers, that means all those folks outside the borders of a given state matter not in the least. This dilemma is at work today where alcohol politics is concerned…just as it was at work between 1781 and 1788, a time during which it was the states and not a federal government that called the economic shots.

I mention this because yesterday was Constitution Day, that 24-hour period each year set aside to celebrate the U.S. Constitution and teach it in federally funded schools. It would be nice if students learned that the reason Americans abandoned the Articles of Confederation in 1788 for the U.S. Constitution was due primarily to the self-centered and self-interested ways states during the periodl of the Articles of Confederation that led to economic confusion, economic downturn, and chaos amongst the states.

The Articles of Confederation, officially adopted in 1781, was the national governing structure under which the various states operated both during and after the Revolutionary War. The Articles provided for a very weak federal government that neither had control of foreign policy nor interstate commerce. Nor was there a reliable mechanism for raising funds for the national government. It didn’t take long for the weakness of the United States under the Articles of Confederation to become apparent.

Its weaknesses became most apparent when different states began erecting tariffs and passing taxes aimed at both international commerce as well as at other states. State tariffs and taxes aimed at protecting the industries in individual states were erected up and down the former colonies. State currencies emanated from various states causing varied levels of inflation when paper money was printed when needed and often in significant amounts.

It was this frustrating economic protectionism practiced by the states under the Articles of Confederation that led directly to calls for a constitutional convention that was meant to create a new national government that would have the power to eliminate interstate trade wars and regulate commerce between the states. That Constitution went into effect in March 1788.

In its final form, the U.S. Constitution included Article 1, Section 8, known as “The Commerce Clause”, which states:

“The Congress shall have power to… regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes”

With these 21 words, the individual states ceded the power to the federal government to regulate trade between the states, ending the chaotic economic mess that defined the national economy under the Articles of Confederation.

Flash forward 145 years to 1933 and the ratification of the 21st Amendment ending national Prohibition. In the second paragraph of that brief Amendment to the Constitution, it was declared:

“The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.”

“…of the laws thereof…”

On its face, these words look like an invitation to the states to regulate interstate commerce in alcohol. But what about the Commerce Clause?

It should be no surprise that state lawmakers, being state lawmakers and knowing where their bread is buttered and who delivers it, did indeed begin immediately enacting laws that regulated the interstate commerce of alcohol. With that kind of apparent power put in their hands, lawmakers just couldn’t help themselves in the same way that state legislatures during the period of the Articles of Confederation couldn’t help themselves and went about enacting laws to protect their own in-state industries to the detriment of out-of-state interests.

And those state laws regulating interstate commerce in alcohol lasted for a time; just up until about the moment that wineries, brewers, and distillers started to proliferate and notice that states other than their own were actively hampering their ability to engage in interstate commerce.

It took 72 years from the ratification of the 21st Amendment with its seemingly broad grant of powers to the states to regulate alcohol, for the U.S. Supreme Court to finally reign in what had become naked attempts by states to discriminate against out-of-state alcohol interests for the sake of their own producers, wholesalers and retailers.

In 2005, the Court heard a case that challenged the laws of New York and Michigan that allowed in-state wineries to ship their wine directly to consumers in their state but denied the right to out-of-state wineries. The out-of-state wineries challenging the law reminded the Court and the states of Michigan and New York that the Commerce Clause gives the federal government, not the state governments, the right to regulate interstate commerce. And by blatantly discriminating against out-of-state wineries, that was a sure attempt to usurp from the feds their explicit right to regulate commerce between the states.

As you might imagine, New York and Michigan (along with wholesalers in those states) piped up and said “Wait just one minute…please read the 21st Amendment…You know, the one that says it’s our laws, the states’ laws, that can’t be violated by out-of-state interests.”

This is what Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for a 5-4 majority in the 2005 Granholm v Heald case had to say about that:

Time and again this Court has held that, in all but the narrowest circumstances, state laws violate the Commerce Clause if they mandate “differential treatment of in-state and out-of-state economic interests that benefits the former and burdens the latter.” This rule is essential to the foundations of the Union. The mere fact of nonresidence should not foreclose a producer in one State from access to markets in other States. States may not enact laws that burden out-of-state producers or shippers simply to give a competitive advantage to in-state businesses. This mandate “reflect[s] a central concern of the Framers that was an immediate reason for calling the Constitutional Convention: the conviction that in order to succeed, the new Union would have to avoid the tendencies toward economic Balkanization that had plagued relations among the Colonies and later among the States under the Articles of Confederation.

It only took 14 years for the Supreme Court to reiterate Kennedy’s history lesson when in 2019, Justice Samuel Alito took Tennessee to task for another example of trying to use the 21st Amendment to justify discrimination against out-of-state alcohol companies with its law that required out-of-state retailers to become residents of the state for two years before opening a store. Writing this time for a 7-2 majority in Tennessee Wine v Thomas, Alito reminded:

Removing state trade barriers was a principal reason for the adoption of the Constitution. Under the Articles of Confederation, States notoriously obstructed the interstate shipment of goods. “Interference with the arteries of commerce was cutting off the very lifeblood of the nation.” M. Farrand, The Framing of the Constitution of the United States 7 (1913). The Annapolis Convention of 1786 was convened to address this critical problem, and it culminated in a call for the Philadelphia Convention that framed the Constitution in the summer of 1787. At that Convention, discussion of the power to regulate interstate commerce was almost uniformly linked to the removal of state trade barriers, and when the Constitution was sent to the state conventions, fostering free trade among the States was prominently cited as a reason for ratification. In The Federalist No. 7, Hamilton argued that state protectionism could lead to conflict among the States, and in No. 11, he touted the benefits of a free national market.

Last week a New Jersey winery and a New York retailer sued the state of New York for, you guessed it, regulating interstate commerce in violation of the Commerce Clause in the interest of protecting in-state interests. In this case, New York allows its wineries to forgo the use of a wholesaler and sell directly to New York retailers and restaurants. However, New York bans out-of-state wineries from going around wholesalers and selling directly to retailers and restaurants.

This is an old law. However, after two Supreme Court decisions in the past 20 years, you’d think New York would have the sense to change its law because, well, it’s obviously unconstitutional. But, state lawmakers will be state lawmakers.

The National Association of Wine Retailers, a nationwide trade group that believes Justices Kennedy and Alito got it right (and for which I serve as executive director), recently issued a press release to the media, state alcohol regulators, and the alcohol trade urging the Attorney General of New York to settle this case rather than wasting taxpayers’ dollars defending a clearly unconstitutional law. We’ll know in about a month if that is the route chosen or if they decide instead to challenge the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Similar laws that usurp the right of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce and that promote discrimination and protectionism exist all across the country in state after state. These laws bar out-of-state distilleries, wineries, and breweries from selling to their retailers while allowing their in-state producers to do so. Their laws bar out-of-state alcohol retailers from selling directly to consumers in their state while allowing their own in-state retailers to do so. And numerous states bar out-of-state producers from shipping their products directly to consumers in their state, while allowing their own producers to do so.

State lawmakers can’t help themselves. It’s a function of electoral politics. When faced with the prospect of being able to help their constituents at the expense of legitimate out-of-state businesses they will choose the Articles of Confederation every time.