New World Laissez-Faire Winemaking Is Changing Old World Wine

Turns out Freedom is exactly what's called for in the wine world

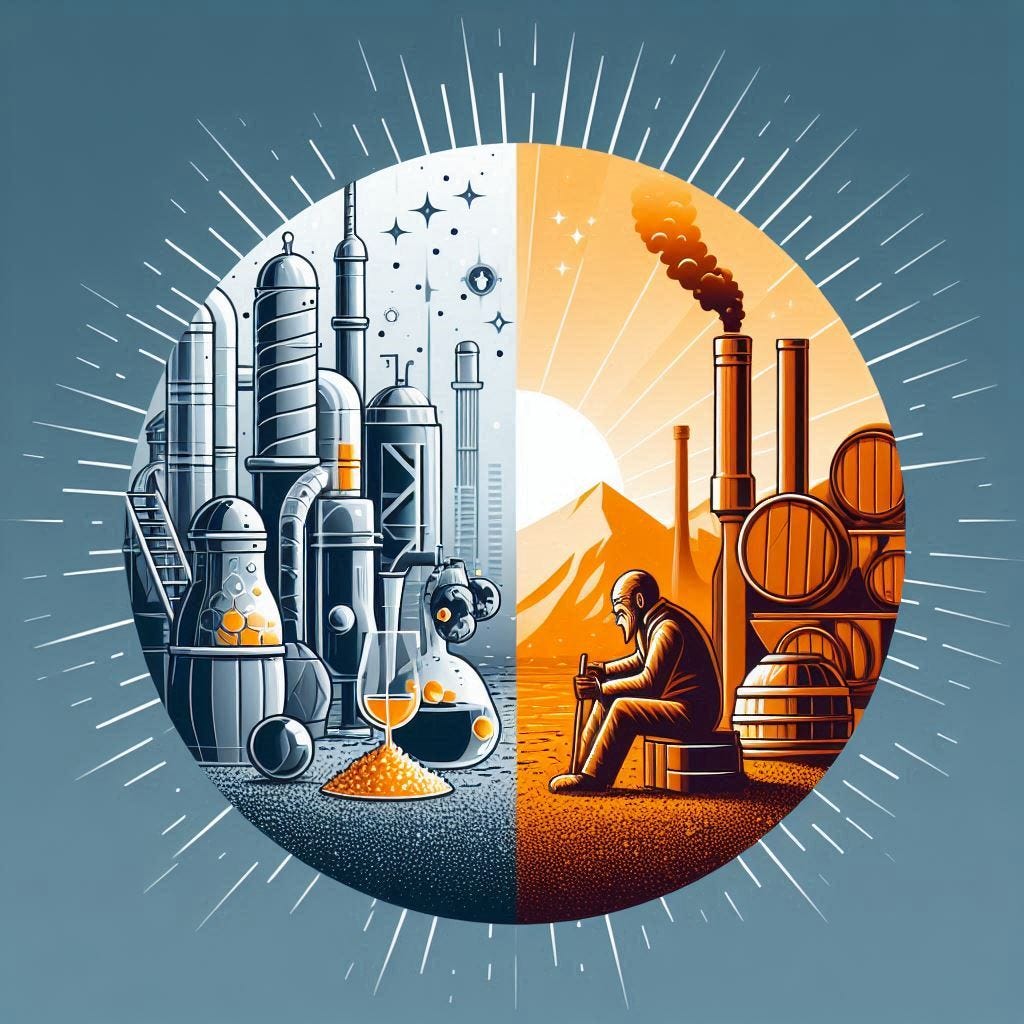

A longstanding hallmark of the American wine industry dictates that wine can be crafted in any way the vintner wants, using any techniques they desire, and with any grapes they want—so long as the truth about where the grapes were grown and the alcohol content is accurately placed on the label. Compared to the Old World, this is a decidedly laissez-faire (American) approach to the ancient art of making wine: freedom over constraint and experimentation over tradition. It appears Europeans are discovering the benefits of this approach.

Try to imagine for a moment the reaction to a proposed law dictating that any red wine made carrying the “Napa Valley” appellation on the label may only be made with some combination of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc or Petit Verdot. Furthermore, the proposed rule dictates said “Napa Valley” wine may only be made from grapes that are picked at 22.5 brix of sugar content or higher and must be aged in oak barrels for no less than 8 months.

That vision you are having of Napa winemakers, winery owners, and vineyard owners parading their trucks and BMWs to the halls of power to tell these lawmakers to fuck right off, while comic, is probably a pretty accurate depiction of the kind of response such a proposed rule would generate. This kind of rule is about as anti-American as can be imagined. Yet these are exactly the kind of rules winemakers in France, Italy, Spain, and other Old World winemaking countries have lived under for decades.

That appears to be changing, according to a recent article in Wine Enthusiast written by Jacopo Mazzeo.

Since their earliest modern manifestations in the first half of the past century, geographical indications (GIs) have been instrumental in shaping people’s understanding of wine.

They provide drinkers with a level of confidence regarding the origin of grapes and adherence to safety standards. They are also strongly associated with the perception of quality: The more stringent the regulations and circumscribed within a geographical area, the more accurately they are thought to reflect a wine’s terroir expression.

Generic table wines like France’s vin de France and Italy’s vino da tavola, which instead offer producers considerable freedom, have traditionally been associated with more affordable and lower-quality options.

While somewhat accurate overall, such a simplistic, binary interpretation has been gradually losing its relevance. A growing number of winemakers around the world have strayed from the constraints of GIs in favor of more freedom and creativity in the production process.

Back in the day, there was a certain logic to requiring wines produced with specific appellations on their labels to adhere to strict rules dictating which grapes could be used, when those grapes could be harvested, how closely vines could be spaced, what brix level grapes must achieve, or how long and in which kind of oak barrels the wine must be aged within. These rules determined generally what a Haut-Medoc, Chambolle-Musigny, or Champagne would taste like. It is a form of consumer communication as much as a regulatory diktat. With these vine-growing and wine production rules in place for various appellations, consumers would eventually learn by experience what to expect from the wine, even without knowing anything about the producer. All they had to know was the place of origin listed on the label.