A Response to Wine's Diminishing Place in the Society

How a better kind of wine communications can help stave off decline

There is and has been for some time, a distinct feeling in and around the wine world that wine is losing ground; that its share of the consumer mind and pocketbooks, is being diminished from what it always has been. I think those feelings are based on sound observations and grounded in reality. And the question arises, is there a response that can stave off further erosion of wine’s place in society? There is.

First, let’s look at the type of advantages that wine has long held over other alcoholic beverages. For decades following the repeal of Prohibition, there have been three essential types of alcoholic beverages: wine, beer and spirits. Beer was long the popular favorite having to do with many cultural and social circumstances, not the least of which were the countries of origin for immigrants to America, the types of crops that best grew on American shores from the time of America’s founding, and peculiarities as well as logistics surrounding the alcohol distribution systems existing both pre-and post Prohibition.

Spirits have a similar advantage over wine. Its production didn’t depend on growing difficult crops. Its raw materials either in the form of types of sugars or grains were more easily accessible.

Wine however was based on a crop that didn’t take well to early American soils. Moreover, immigrants who came to these shores were not predominantly from wine-producing countries like France, Italy, and Spain, but rather from spirits and beer-drinking countries like England and Germanic countries.

But wine always held one distinct advantage over beer or spirits: it was a far more interesting drink. It was the product of a singular growing season and not produced from a constant supply of easily obtainable raw materials. Wine drew a direct connection to a specific place and time. Unlike beer and spirits, the folks that produced wine often grew the raw materials. These people were more than brewers and distillers. They were also farmers and farmers for most of human history were atomized, individuals overseeing the crops on a relatively small plot of land they took great care to husband and cultivate in very localized ways.

Wine is also more interesting because of its variety and diversity. Distinctly different types of wine are produced in small localized territories, while the different types of wine increase even further as you go further afield from a specific place. The wines of Portugal are diverse, yet entirely different from those of the Languedoc, which are distinct from the wines of Burgundy, which are distinct from the wines of Bordeaux, which are distinct from the wines of Champagne. And we are not yet even thinking about the diversity and variety of wines from Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Australia and, of course, the United States.

The other level of diversity beyond the location where the wines are made is the terroir of where the grapes are grown. Looking just at that small place called Sonoma County and you see that the terroir of Bennett Valley is different than its next-door neighbor, Sonoma Mountain, which is quite distinct from the floor of the Sonoma Valley, also next door.

Finally, on top of all those things, consider the variety of people who chose to grow and/or produce the wine. Suffice it to say, the variety and diversity of this group, their roots, their history, their aims, and their philosophies make them distinct elements of what makes wine more interesting than beer or spirits.

Because wine is more interesting than beer or spirits, it has always been a more common subject for storytelling. When I entered the wine industry in 1990 and for years before that, far more ink was being spilled on the subject of wine in order to entertain, educate and inform folks than was being devoted to beer and spirits. In 1990, the idea of a “wine writer” was commonplace. But “beer writers” or “spirits/cocktail writers” were highly unusual.

I can give you a concrete example of just how great was the diversity and variety of wine just looking back over the past twenty years.

In the year 2000, the Federal Government approved 53,792 different alcoholic beverage products for sale in the United States. Of those, 85% were wines. Seven percent were spirits and 8% were beer.

Fast forward to 2021 and we find that the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) approved a total of 178,724 individual alcoholic beverage products for sale in the United States. However, only 63% were wine, 24% were beers and 12% were spirits.

Wine has been losing its diversity and variety advantage over its main beverage competitors and there is no sign that the diminishment of its advantage is going to end soon.

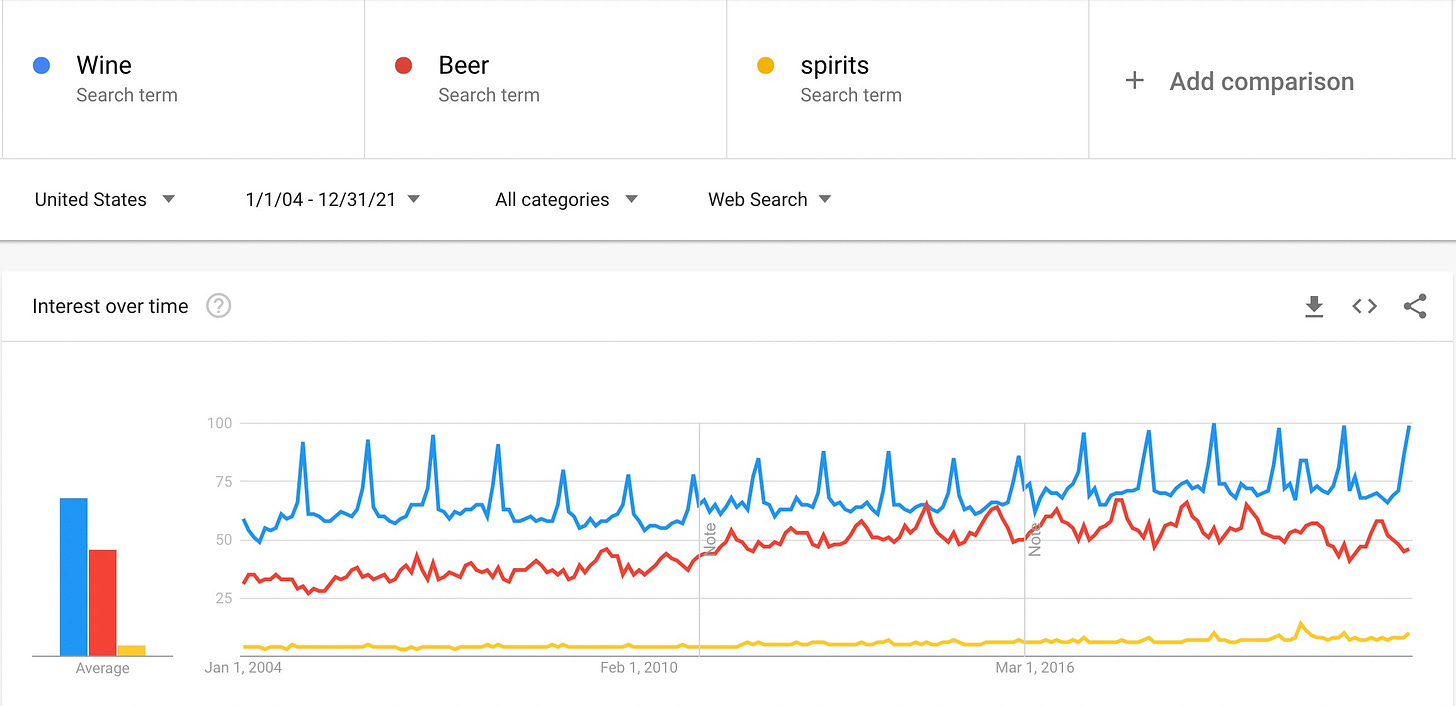

It should be no surprise, that over the past two decades the amount of editorial coverage beer and spirits have received in the media has increased significantly. Below is a graph showing Google searchers for Wine, Beer, and Spirits from 2004 to 2021. Note how searchers for beer and spirits have accelerated at a faster pace than those for wine.

And yet despite the increased coverage for beer and spirits, the increase in the diversity and variety of beer and spirits, and the increased consumption particularly of spirits, wine remains the far more interesting beverage for all the reasons I’ve outlined above. It is this singular advantage of being a more interesting product than beer or spirits that provides wine the opportunity to reverse its decline in both sales and coverage by the media.

Yesterday on Twitter there was a short discussion among a few people that began with the following question by Chasity Cooper, an excellent wine writer:

“Are you hopeful for our [wine writing] niche to keep evolving and expanding, or has it reached its peak?”

This is the kind of question that concerns me in general having spent three decades working in the wine media milieu primarily as a publicist but also writing a blog/newsletter for nearly 20 years. It’s also the kind of question that touches on the state of the wine industry and the media’s relationship to that industry. My response to Ms. Cooper was as follows:

“It will continue to evolve, Chasity. However, expansion is more doubtful. You would need to convince media orgs that have many eyeballs to spend money on wine coverage. It's been going in the other direction for many years.”

I absolutely believe that part of the puzzle to counteract the relative decline of wine sales and wine consumption is finding a way to increase the relative attention paid to wine in the media. Furthermore, the only path to increasing coverage of wine by the larger media outlets as well as smaller outlets and individuals is by leaning into the fact that wine is the most interesting beverage in the world. So the question becomes HOW do you go about re-engaging the media and media types with wine and convincing them that the stories, diversity, and variety of products are so compelling they must be covered and explored more regularly?

Finding a novel way for the media to engage with wine is of course very difficult. It’s difficult because the product is fairly unchanging. There is only so much you can do with grape juice and yeast. The product, wine, is not going to evolve. While the centers of production may change and evolve over time, wine will remain wine, farmers will continue to farm, and wine will remain, at its best, what it always has been: a consumable link to a particular place and a particular moment in time produced by a particular person or people.

Don’t get me wrong, this is a very unique set of properties. And when you consider that the best wines evolve over time, you have another unique feature of the product: not only does it point to a time and place, but it’s also alive. Still, the question remains, how can wine be reframed to become something of heightened interest to editors, communicators, publishers, and writers?

There was some suggestion in the Twitter conversation that part of the problem or at least part of the issue at hand is the fact that younger folks don’t control the direction of wine communications and if they did things might be different.

Brianne Cohen is a certified sommelier, wine educator, consultant, and writer based out of Los Angeles who has demonstrated a knack for insightful, clear, and interesting writing about wine. She had the following to say during the Twitter discussion:

Yes, I think my/the niche of fun and approachable communication about wine will continue evolving/expanding. “Young people”/the new generation will eventually move into positions of power ie editors and writers, which will force the comms to evolve. We talk about younger gens seeking authenticity and storytelling in mktg/sales yet so much of what we’re giving them is “10 wines to pair with candy cane” type stories. I think there’s an opportunity for more rich storytelling that is more cultural/lifestyle rooted vs wine rooted. To “us” wine is the main character. To the rest of the world, it plays a supporting role. Also, I think there’s an opportunity for more clear, easy to understand wine recommendations (ie listicles) that focus less on traditional tasting notes and more on “why this is a dope wine” that you need to try. Bottom line. I’m excited. I’m excited to see where/how this industry and writing about this industry evolve. The cultural influence of this drink is remarkable, so as our world evolves, so will wine.

While I don’t agree with Brianne that a younger set of eyes on the industry can produce a more interesting kind of communication about wine than an older set of eyes, I do think she has very good insights into the kind of wine storytelling that is more likely to appeal to a wider audience.

Brianne’s emphasis that cultural/lifestyle editorial associated with wine is the correct pathway to more interest in wine editorial seems spot on to me. But it’s not a coincidence that this kind of writing about wine is also the most difficult. Bringing the complexity and diversity and uniqueness of wine outside the context of the grower/producer/region and placing it into the wider milieu of culture and society and politics and economics is rarely attempted. The effort would take a highly skilled writer and observer who is able to make the insightful connections that are to be found between wine and society and culture at large. But, this is the ticket.

Finally, it is one thing to convince really good writers and communicators to embark on an effort to create editorial that places wine in a broader, more interesting social and cultural context. That’s hard enough but doable. The other challenge is convincing the editorial gatekeepers that this kind of writing as well as more pedestrian and common wine writing ought to be showcased in their publications, articles, and productions more regularly.

There is no concerted, industry-wide effort to promote wine to the media. This is a shameful deficiency in the marketing efforts of the American wine industry and each of its constituent parts. As I’ve said before, part of the challenge for the Wine industry is to create some type of body that can collectively promote wine drinking. Such a thing is a multi-million, multi-year effort that can only be appropriately funded by producers, wholesalers, and retailers, and importers together. Clearly part of this kind of effort would be a media relations arm focused entirely on urging editors and producers to focus on wine more regularly.

The alternative to creating this sort of promotional body, and with it an effort to see more compelling cultural/social commentary on wine, is hopes and prayers. This is a very bad strategy and not much in the way of an alternative.

Still, the idea of seeing Cohen’s call for more cultural and social context in the world of wine writing is compelling. The hope is that some small set of writers and producers will emerge who can demonstrate the utility of this kind of editorial and sell their vision to a larger audience. The prayer is that if and when this effort emerges it will motivate other communicators, writers, and producers to create an equally compelling bit of storytelling that can convince thoughtful Americans that wine is the truly uplifting and the most interesting beverage that can make them and their own lives more fulfilling and more interesting.

Great article, Tom. Let me point out that wine writers in general are reluctant to tell the story of the 99% of wineries that don't participate in the three-tier system. I refer to the 12,000 wineries averaging 2,000 cases that are making the most interesting wines in the world, primarily from varieties and regions that didn't exist forty years ago.

It baffles me that top wine writers but rarely discuss the best Iowa La Crescent, Missouri Norton and Vignoles, Minnesota St. Pepin, New York Aromella, Pennsylvania Vidal Blanc, Wisconsin Seyval Blanc, Illinois Cabernet Dore, Kentucky Crimson Cabernet, Indiana Traminette...I could easily list 40 well-established varieties. And then there are the newbieslike Ikalto, Nokomis, Zinthiana, Arondell, Petite Pearl, and more each year.

I believe the invisibility of this ongoing and rapidly growing sector right under our noses can only be attributed to cowardice and a touch of vinifera racism. Writers are either afraid to stick their necks out in fear of blowback from their readers or they have failed to do their investigative homework and are utterly unaware of what goes on outside the three-tier system's megaboutiques, the majority of which are supplied by a mere 65 American wineries over 500,000 cases.

While these giant wineries are losing share since they provide nothing more than a pleasant buzz, the small guys are growing leaps and bounds because they are the real deal, as you have described.

Wine is much more interesting -- simply tastes so much better -- when you know the people who made it and have heard their philosophy and motivation for making their wines the way they do. The best part about these small wineries is that you can make a personal connection with Mom and Pop and their dog by visiting a winery near where you live. Try that with Robert Mondavi or Jess Jackson, even when they were alive. As an entree to this world, I strongly recommend the movie Wine Diamonds, which tells the story of five midwestern family wineries.