Substituting Thoughtfulness for Defensiveness

The impact of problem drinking can be diagnosed with real facts and analysis or with acts of self-preservation

The consequences of both isolated instances and lifetime pursuits of excessive consumption of alcohol are many. In America, numerous policies and initiatives have been instituted to address both kinds of excessive drinking from laws governing the closing hours for bars to constitutional amendments. What’s rare is to see a comprehensive explanation of the causes of excessive drinking such as that produced recently by writer Jill Filipovic. What’s more common is encountering the absurd claims explaining dangerous consumption offered up by the likes of Utah lawmakers who insist we curb excessive drinking through government regulation of alcohol distribution.

Responding to a proposed ballot initiative that would get the state of Utah out of the business of retailing alcohol and curtailing direct-to-consumer shipments of wine, Utah State Senator Jerry Stevenson said the following:

"I would think it’s not a good idea for the state of Utah. You’ve heard me say this lots of times. We're the lowest in the country as far as drunk drivers. We're the lowest in the country as far as our youth getting hooked on alcohol.”

The Senator here is claiming that Utah law making the state the distributor and retailer of alcohol is the reason for Utah’s low rates of drunk driving and youth alcohol consumption. No mention here of the fact that the population of Utah is made up of 66% Mormons—a religion that forbids alcohol consumption. One might, upon considering the unique culture of Utah, conclude that this huge percentage of the population that adheres to a faith that bars alcohol consumption is the reason for lower rates of drunk driving and youth alcohol consumption. Instead, Senator Stevenson suggests fewer folks drive drunk and fewer minors drink alcohol in Utah because they are buying their booze from the state, rather than a private business.

It’s difficult to identify a greater misplacement of causation than that offered by Senator Stevenson.

We see this kind of misplaced causation among lawmakers and alcohol industry players all the time. The assignment of virtuous outcomes from the three-tier system of alcohol distribution is put forth regularly. Wholesalers who benefit financially from a three-tier system of alcohol distribution work hard to assign social and cultural value to a system they benefit from financially. Meanwhile, lawmakers assign health and safety benefits to the system they profit from by doing the bidding of wholesalers. Regulators defend the three-tier system on bogus health, safety, and law enforcement grounds when their jobs largely depend on continuing to enforce and regulate this system.

All of this unfounded assignment of causation is understandable. We often simply do and say what benefits us personally. But these acts of self-preservation get us nowhere near to understanding why unhealthy alcohol trends may or may not be advancing in society.

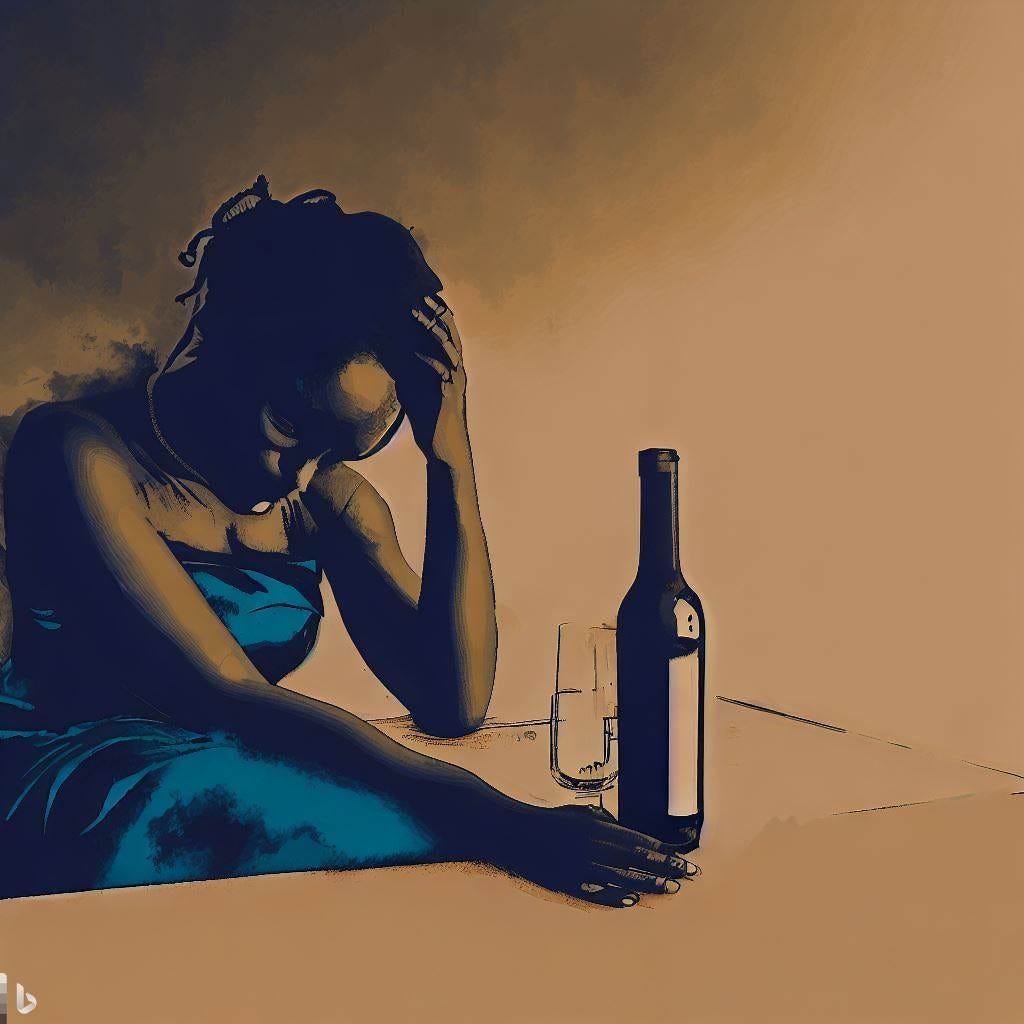

This brings me to Jill Filipovic, the writer who recently penned an insightful opinion piece for CNN entitled, “American women have an alcohol problem. It’s critical to understand why”.

It turns out that between 2018 and 2020, alcohol-related deaths among women have increased by 14.7% (males have seen a slightly lower 12.5% increase). Had Ms. Filipovic wanted to, she could have pointed to the increase in alcohol-related deaths and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and left it there. But this approach, similar to assigning some magic causative effect to buying alcohol from the state, would not come close to telling the whole story, which must take into account long-term cultural and societal evolution and political trends to fully understand what is happening with women (and men) and alcohol.

Filipovic’s willingness to look at broader trends begins with this early observation in her opinion piece:

“These findings go hand-in-hand with other indicators of physical and social decline for women and men: a decrease in life expectancy more broadly, and particularly among working-class White Americans; elevated rates of suicide and drug overdoses; and upticks in depression and anxiety. More Americans than ever are living alone, and while that could be a potent social shift with benefits for some, for a lot of other people it means less empowered singlehood and more isolation, including the depression that can come from feelings of loneliness and disconnection.”