Randy Caparoso: The Ramble

A Great Ramble With Marketer, Writer, Photographer Randy Caparoso where we agree to disagree

Where Randy Caparoso is concerned, I’ve always felt like a voyeur. I’ve known of him my entire wine career. I’ve read his articles and essays my entire career. But despite all this, having regularly seen his picture, and always thinking, “damn is he baby-faced”, I’ve never had a conversation with the man. Then early last week I read, “We Need To Talk About Wine In An Intelligent Way”, published at Wine Industry Advisor.

In the article, Randy takes apart the wine industry for, in his view, treating consumers as though they are idiots, dust, easily manipulated money dispensers. Randy wrote this:

“The dumbing down came a lot earlier, probably somewhere in the 1970s and 1980s, when wine media began adopting the standard wine industry attitude that wine consumers, in general, are of low intelligence. Consumers “think dry and drink sweet,” it was always said. Also: they are incapable of understanding, much less appreciating, more than three, four, maybe five different “varietals” at a time. And if you lavish wines with oak qualities, whether through barrel aging or profligate oak amendments, consumers will love it….Consumers would be a lot more sophisticated today if we had given them more credit from the very beginning, acknowledged them as being capable of absorbing information and understanding all the wonderful complexities and nuances that make wine appreciation so compelling.”

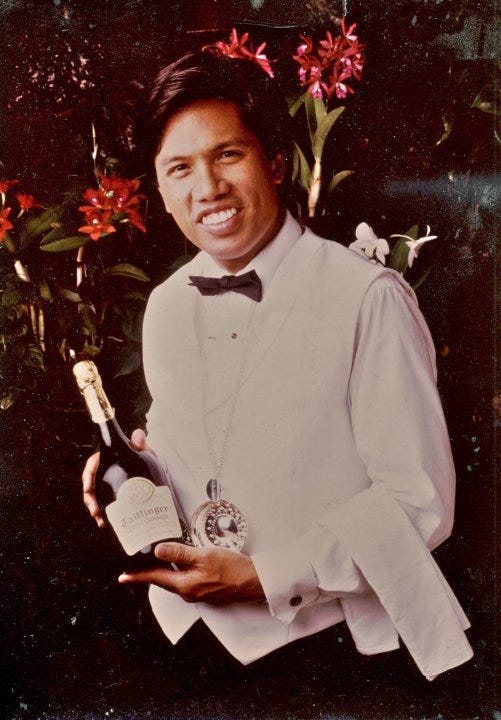

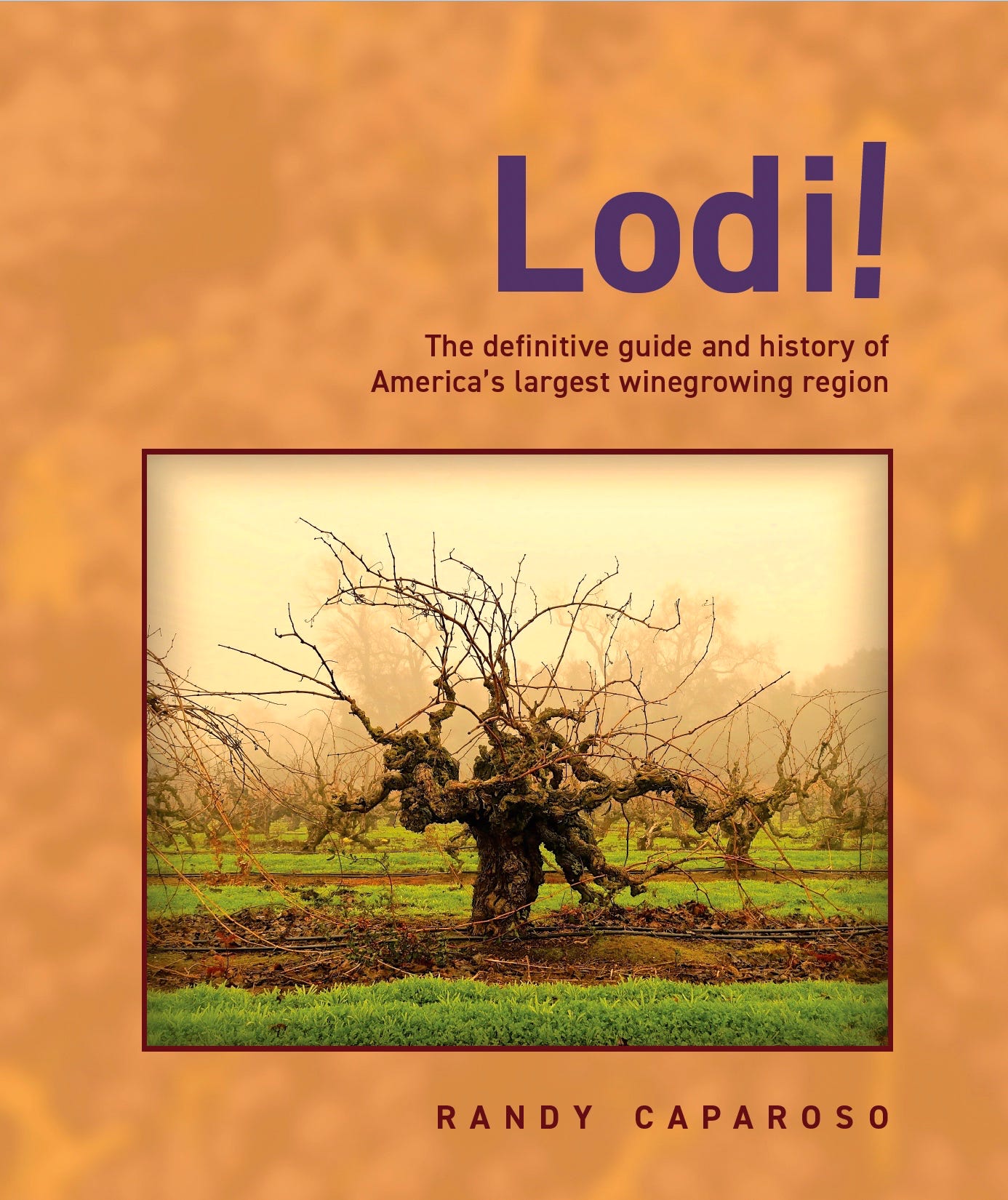

Randy made a great argument for the idiocy not of the consumer, but of the wine industry as a whole. And he is equipped to do so. He began working as a Sommelier in Honolulu in 1978, and was a founding partner of the Famed Roy’s Restaurants where he was VP/Corporate Wine Director for 13 years. Wrote the wine column for the Honolulu Advertiser for 20 years, went on to write, blog and become an award-winning photographer, has worked and written for the Somm Journal since 2008, and recently saw published, “Lodi! The Definitive Guide and History of America's Largest Winegrowing Region.” His career bleeds “Wine Authority”.

His article taking to task the wine industry in Wine Industry Advisor didn’t agree with my own view of the industry. But, again, it was so well argued. I wanted to draw Randy out more on the issue. So, I invited him to Ramble with me. You’ll find Randy has a great deal to say. I urge you to read the Ramble all the way through. You are going to get to know someone who has much more passion than most, is more articulate about his passions than most, and who has more to say on the subject.

This interview approach, “The Ramble”, begins with one question emailed to the subject. They respond in any way they choose, which in turn prompts my next question, and so on. It is a less formal way of conducting an interview, results in something a bit messier and rambling, but also produce something more interesting and authentic I think.

TOM: Thank you for taking this ramble with me, Randy. I’ve followed your work and your regular commentary on the industry for a very long time. As I mentioned to you in an email, this Ramble was inspired by a recent article you wrote for Wine Industry Advisor in which you admonish the wine industry in America (mainly the media, really) for treating consumers as though they are low intelligence and incapable of appreciating the wide diversity of wine that exists in the world. I thought it was a brilliant article, though I don’t agree with much of what you wrote. So I want to draw you out on this topic. But first, let’s chat a little about the state of the wine industry in the U.S. I contend that U.S. wine consumers find themselves in a “Golden Age” of wine drinking in which anything and everything at nearly every price point is laid out in front of them. Am I wrong?

RANDY: Unquestionably, we are living in something of a “Golden Age” for consumers, both connoisseurs and casual wine lovers, not just in the U.S. but all around the world. Wine quality the world over has never been higher, and there has never been more access to a nearly endless variety of wines. The global wine industry's growth has begat more consumption, and consumption continues to drive the wine production around the world. And everyone is so damned spoiled because of that.

Ironically, it was back in the 1970s, when I first started in the wine business as a sommelier, when Robert Mondavi was often quoted as saying we were living in a “Golden Age," although he was speaking specifically in terms of California Wine. The “discovery” of oak, for instance, had Californians convinced they had unlocked one of the secrets that made French wines so special, and vintners and consumers alike were just discovering the significance of vineyard sites, just like the French with their established appellations, from Washington all the way down to Santa Barbara, or in special places like New York’s Finger Lakes. Very exciting times, even if just a small fraction of Americans was actually interested in premium quality table wines in those days, the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s.

And that’s my point: Consumers have always had a humongous thirst for new things. Everyone knows, for instance, that 30 years ago just a tiny fraction of consumers possessed personal computers, let alone understood the technology behind them, or the amazing technology that has since come to pass. When I was hired to write my first newspaper column in 1981, I typed it up, made corrections with Wite-Out, got in my car and drove it all the way down to the newspaper building where it was retyped to fit in with the ads and other articles before going into the gigantic printing press. Thank god we’ve been given the tools so we no longer have to live in this nightmare.

These days, it’s first-graders who are showing their parent or grandparents how to use the technology. They’re mastering keyboards before learning how to use chopsticks! The capacity of the human brain to absorb and use new information is seemingly endless.

So why is it that the American wine industry is afraid of introducing wines beyond the usual choices of Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Pinot Noir? Do they actually believe American wine consumers aren't smart enough to understand, or appreciate, wines made from, say, Ancellotta, Biancolella, Garganega or Mencía? Or grapes such as Mission and Chenin blanc which have been dismissed as “not good enough,” even though they have a long history of producing perfectly good, delicious, appealing wines?

There is a huge range of grapes producing wonderful wines all around the world. But here in the U.S., that range is miniscule—not more than a dozen grapes deemed commercially viable. If human beings are so smart, why, when it comes to wine, do we assume that their brains are infantile? And besides, grapes like Mencía, Biancolella, and Garganega may seem strange in America, but they’re actually everyday stuff in the European regions where they are grown. We could, in fact, probably grow perfectly good Mencía and Garganega here in California because we have ideal climates and soils, similar to European regions. But we don’t, mostly because we don’t think consumers are “ready” for them. This is what I find flabbergasting. It’s not consumers who are dumb, it’s the industry.

I can’t help thinking this because, although I’ve called myself a wine professional for over 45 years, I’ve come about it mostly through the restaurant industry. In one of the restaurants I help found, our chefs cooked 25 to 30 new dishes every night. The methodology was French but the ingredients were global, and so a single dish could have as many as 25 or 35 ingredients, most of which the average consumer might not have never heard of, let alone tasted before. Did that keep guests from being able to appreciate what we were cooking? Of course not. Our restaurants were wildly successful (and still are) simply because the average person appreciates food, and is open to just about anything. That is, the average person is not so dumb that they get lost if you don’t offer just the foods they are used to, like cheeseburgers, spaghetti or chow fun. They crave new dishes—it’s fun, exciting, it makes their day, their week, their year!

This is the crux of my argument, as critical of the industry or media as it may sound. It’s that, if you assume the consumer is super-smart, which of course they are, then you can offer them anything. The more you do, the more they love it. That goes for food, for books, for technology, for music, for everything. Including wine. The entire wine industry—which includes production, trade and distribution, and media—has to start giving consumers credit for brain power. I swear to god, once this happens, the industry will explode, just like it has with the technology and food industries.

TOM: I think it should be pointed out that in France, for instance, two-thirds f acres under vine are represented by only 10 different grapes. In the U.S. The top ten grapes planted appear to account for something in the neighborhood of 60-65% of the acres under vine. I’m not entirely convinced that the American wine industry isn’t offering consumers diversity. That is to say, I’m not sure it’s the fault of producers as it is the fault of the distribution system. But I suppose I should note that I have an axe to grind with the U.S. system of alcohol distribution. But I want to let you flesh out another argument you made in the recent Wine Industry Advisor article. You wrote: "Worse yet, the prevalent thought became that U.S. consumers needed to be presented with a numerical system of wine rating. Consumers couldn’t be expected to possibly understand wines if we went too deep into origins or history, much less differentiating descriptions of vineyards and sensory attributes. No wonder most wine reviews sound alike, more like laundry lists consisting of the same descriptors, simply rearranged. It’s like we’re doing our best to bore consumers to death.”

You don’t seem to have a problem with wine reviews in general, but rather with reviews that include a numerical score. Is this a knock on the 100-point wine rating scale or do you include the puffs, stars and (you will remember this though it is largely gone) the 20–point scale?

RANDY: One of the repercussions of the “dumbing down” of wine for consumers is the narrowing of wine choices, particularly in California which supplies the vast majority of the wines consumed in the U.S.. A little different from France, California’s wine regions are marked predominantly by variations of Mediterranean climate. Theoretically, you can grow well over 100 different wine grapes in California, and grow them very well. We certainly have the climate and soils The reason we don’t, to put it bluntly, is that we don’t think consumers can't appreciate that many. We have to dumb things down for them.

Who is the “we?” I’m talking all of us involved in wine professions one way or another, including production, PR, distribution, trade and media. We’re all responsible for the way we’ve established communication with consumers, hence the marketplace.

This has created certain industry realities which, unfortunately, we’re all stuck with. A big reason why, for instance, Napa Valley is planted primarily to Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, or Sonoma County to Pinot noir and Chardonnay, is economically it’s difficult to plant anything else. Thirty or forty years ago the industry made a commitment to those grapes based upon the assumption that these make the best California wines. By narrowing consumer tastes, the industry painted itself into a corner. Now grape growers have no choice but to plant mostly four grapes, even though they could grow several dozen others that make just as good a wine.

In other words, the industry shot itself in the foot. You can say the issue is complex, but my observation, after over 45 years in the business, is that it’s really pretty simple: It’s because the industry didn’t think consumers were smart enough to understand more than four grapes. That’s what’s shaped the market, making the economics so restrictive in regions such as Napa and Sonoma, which are actually extremely flexible in terms of grapes and terroir.

The economics in regions such as Lodi or Paso Robles, as it were, are not so restrictive. So guess what: When you go to a region like Lodi you find there are actually more wineries selling Albarino and Tempranillo rather than Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. Number one, it’s because Albarino and Tempranillo grow very well in Lodi; and so even though Chardonnay and Cabernet grow just as well, consumers who go to Lodi actually find they like Albarino and Tempranillo better. Number two, this tells you that given the chance, consumers are very open to grapes other than the mainstream varietals. And that’s the point: They have to be given the chance first. You can’t treat them as if they’re idiots who only understand three or four varietals.

The wine world outside of the West Coast, of course, is replete with different wine grapes. Given the chance, wine consumers in other countries have developed a taste for a far wider range of wines than what’s been dominant in California, Washington and Oregon. This is what I mean by approaching our own industry with a little more “intelligence.” If we did, we wouldn’t be narrowing our own possibilities in terms of what we can grow, produce, sell or write about.

100-point systems? This is definitely been one of the most damaging things we’ve done to ourselves. There is nothing wrong with wine reviews in general. We all read reviews on books, movies, music, etc., and this helps us make our buying choices. But you don’t read The New York Times Book Review, for example, to find out 100-point scores. No, you read reviews that thoroughly discuss books, to get the information to guide us in our exploration and appreciation of books. It would be insulting, however, if readers were asked to appreciate books based upon one reviewer’s numerical score, and so it just isn’t done. You read a book review, and you make your own thoughtful decision. No one is holding your hand.

What the mainstream wine media has done is adopt a system that presupposes that wine consumers can’t possibly understand intelligent discussions of wine, and that information on wines needs to be imparted on the basis of numerical ratings. The absurdity is that the world’s finest wines are products of where they’re grown, and those circumstances are nearly endless. Numerical ratings are simply incompatible with this fundamental concept, yet that’s what’s considered standard in our industry.

I get why 100-point systems happened in the first place: It was to make wine appreciation easy for consumers. Okay, that’s been done, but now it’s time to move on. It was time to move on more than thirty years ago. If anything, this has only contributed to the narrowing of tastes which has only hurt the evolution of both consumers and the entire industry, even if the industry is not quite aware of that.

TOM: Regarding the relatively few varieties that are sold to consumers, do you think the wine industry is sort of in a trap now? That is to say, economically a winery or grower is far more likely to safely succeed by planting established varieties and so they do But what about a five-star rating system? Is equally damaging as a 100-Point rating system?

RANDY: Yes, the industry is in a “trap,” painted in the corner, shot in a foot with its own gun, any way you want to put it. A lot of it is setting up the market where we’ve forced consumers to choose among fewer grapes. So that’s what they know, and presumably what they demand. A lot of it is setting up a culture of wine appreciation defined by varietal and brand identification while putting less emphasis on the importance of appellation or vineyards, the way it is traditionally done in Europe.

The 100-point evaluation system has only exacerbated that culture, and the media has played along with it as if this is the “normal” way in which wine—an aesthetic as much as agricultural product—is appreciated. As absurd as saying The Beatles rate a 99 and Grateful Dead just a 90, or The Sun Also Rises is a 95 while The Great Gatsby is a 94.

As I mentioned, there is nothing wrong with wine reviews, wine criticism, or even rating systems (dots, stars, puffs, whatever). If information is imparted, it is useful. The same way, for instance, that standard-issue movie reviews can be useful. Face it, even when movie reviews employ five-point ratings, no one pays attention to the points. We pay attention to the reviews, the words that tell us whether or not a movie might be interesting enough to see. Book and music reviews don’t usually have points or stars at all. The average consumer doesn’t need that. We’re smart enough to figure things out.

What is absurd about what we do in the wine industry is that we’ve set up a numerical system where a rating is supposed to be universal. Something meaningful in itself. When a wine gets a number, it is batted around as if it’s permanent, something attached to a wine for all time, when in reality it is always a number pulled out of the air, usually by one person under one particular set of circumstances. Give the exact same wine to a different person and the number can be drastically different. The other reality that all wines, from the most ordinary to the greatest, taste different on any given day, or at any different time of day. It’s wine, for Pete’s sake, an organic, liquified, alcoholic product made from grapes. We don’t put numbers on books or music, and these things don’t even change like the way wines do after being poured out of bottles!

The point of my op-ed was pointing out the need to change. To start talking about wine with some degree of “intelligence.” If anything, putting numbers on wines is the height of laziness, the opposite of intelligent. If you want to impart information on wines, you need to use the power of human language to talk about them—put a little brain work into it. While 100-point ratings are “easier” to make up or understand, it's the worst thing we can do for consumers because they are intrinsically inaccurate. They don’t give anyone a real idea of whether or not a wine might be good for you. And perpetuating this practice only makes it harder for all of us in wine-related businesses to increase the appreciation of wines. No wonder the American wine industry is only about four or five grapes when it can be about so much more!

TOM: I think of the 100-point rating scale (and all rating scales for that matter) as adjectives, an impression delivered in numerical form that adds color to the written review. Also, wine is quite different from film. The variety of film is infinitely greater than wine. While most people can tell the difference between one film and another, many, many people can’t identify the difference between two red wines. Moreover, far more wines are released in a given year than there are films. If a reviewer or wine publication wants to try to do Justice to the many wines available, they can’t delve into the various nuances in cultivation, winemaking, and people in each review. My view is that for a certain type of wine publication, reviews with ratings serve a purpose. And, many folks seem to appreciate it. But I want to bring you back to your notion of talking about wine with some degree of intelligence.” I’m thinking about the media now. Just as I think we are in a true golden age for wine consumers, I think too that we are in a golden age of wine writing. You and I have been around the industry a while and I think we both would agree that the amount of wine media has expanded exponentially. But this doesn’t matter if what we are reading is dreck. You’ve been consuming wine media for decades; back when the gates to the wine publishing realm were tightly locked. It’s different today? Is the wine writing we are exposed to today mainly dreck?

RANDY: We will have to agree to disagree on the usefulness of wine ratings, Tom. The overall culture is to present wines as if they are all in some kind of competition. I find that offensive and more and more people in wine-related businesses are in agreement with me on this. The finest wines are expressions of where they are grown, as well as the talents of the people who grow the grapes and craft the resulting wines. Putting a number on well-crafted is not just offensive to me, it's offensive to the wines themselves.

This, in fact, is what I mean by dumbing down where it involves wine media. I would not describe these times as a “golden age” of wine writing. Every generation probably believes they are in some kind of golden one, and every generation would be dead wrong. Every generation is in their own age, not one that is better than before or better than what is still to come.

The same goes for wine itself. Yes, a lot of what we see today is commercialized dreck, which doesn’t keep a lot of what we see today from being amazing. In fact, the way things are going, I don’t think it’s any stretch to say that in the future wines in general are bound to be a lot better than what we are seeing today. No, we were not in a “Golden Age” 50 years ago when Mondavi used those terms, and we are not in a “Golden Age” today. Despite environmental challenges, there is every reason to believe that future generations will be smarter than us, more resourceful than us, and most certainly good enough to produce finer wines than ever before.

Insofar as writing, there are, in fact, a good number of journalists today who are as talented and perceptive as the Hugh Johnsons, Gerald Ashers or Kermit Lynches who came before them. Yes, for me, these would be the ones who write about wine in terms of where they’re grown, the history of places, and the meticulous labor going into them. The ones I have in mind don’t fall into the usual trap of discussing wines as if they were in a contest, or feel the need to rate them like cars in automobile magazines.

TOM: Try to imagine what kind of life a public person would live if they never agreed to disagree. Brrrr. Also, Gerald Asher…I miss his articles. But I never let the subjects of my Rambles make note of the folks they admire without them naming names. Who are some of the writers working today who you admire, who can inspire you, who can tell the story of a place and their wines?

RANDY: I was afraid you’d ask me that, Tom. If I say four or five names, a good twenty or thirty might say, what about me? This reminds me of my old chef/partner Roy Yamaguchi, who was something of a celebrity. We always told him it wouldn’t hurt if once in a while he’d step out of the kitchen and say hello to some super-valued customers. He always said that if he did that, everyone else around would ask, what about me? Then he’d never get back in the kitchen! So he never did.

Bill Clinton once visited our restaurant when he was still in office; and of course, he started shaking hands of guests. I swear to god, he shook each and every person’s hand (we sat 150 at a time).

In any case, since you asked, here are some writers (not all!) I actually enjoy reading: I think Kelli Audrey White is one of our best writers today, adept at numerous subjects, dogged enough to do the research (preferably firsthand for her), and able to dive deep and accurately. Elaine Brown is almost always equally perceptive and dedicated in her coverage of a huge range of subjects.

The East Coast writers, Lettie Teague and Eric Asimov, certainly demonstrate good insight with a lot of chops, even within the limitations of “short” columns issued from their respective command posts. Closer to home (inland California), I’m a huge fan of Mike Dunne; a rarity of a writer who actually goes to the places he covers, and speaks plainly and without preconception, whatever the subject.

While he leads a magazine (Wine & Spirits Magazine) driven by 100-point reviews, I’ve always admired Joshua Greene’s easy ability to get at the heart of wines, vintners, and vineyards. I’ve been told that he personally abhors the point system, but has obviously made peace with it long ago.

As bloggers go, Alder Yarrow spins a good yarn. I love his perspectives on the wine world in general, plus the fact that you can depend on his consistent standard of integrity.

But really, after all these years, I am probably most entertained by simply reading the Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant newsletters. Kermit himself no longer writes the bulk of it, but the entries are still models of brevity, capturing the essence of wines, places, and people. You can *taste* the wines in the prose, something only the rare legends, Hugh Johnson and Michael Broadbent, were once able to do; proving that there is no need for numbers and long lists of imaginary (i.e., delusional) descriptors when you just make crafty use of words to talk about what’s important.

TOM: Your collection of great wine writers closely matches mine. I’d add Matt Kramer, the former columnist for the Spectator and author. I keep going back to his insightful work.

OK…I have one more question for you to end this ramble. I know now why I was captivated by your article despite disagreeing with some of it. You write and think with a kind of passion that marks you as a deep thinker. That’s the sort of thing that inspires me. So, I want to ask you a question I’ve never asked a subject of a ramble: Why do you love wine?

RANDY: If, as you say, I’ve struck you as a “deep thinker,” you would think that you wouldn’t have to ask why I’ve harbored a passion for wine as a subject, and wines for the pure pleasure of their taste, ever since I was first exposed to them while working my way through college in restaurants back in the mid-1970s. It comes down to this: Virtually all wines appeal to the intellect as much as the senses. Personally, I’ve always dug the “thinking" side of wines, and later (becoming a full-time sommelier at age 21) the thought process needed to succeed in the wine business itself.

However, wine is not just artistry, a craft, or an engrossing science—the things that men and women feel they can control through their minds and labor. There is also the beauty of that direct connection to Nature—where and how wines are grown, the absolute tyranny of vintages, the decisive impact of the environment itself, whether it’s in tiny corners of individual vineyards or broad swaths of entire regions. The fact that both Nature and toil can be crystalized in a bottle, and most definitely perceived as sensory manifestations once poured into the glass, is what has made wine so compelling to countless wine lovers for hundreds, make that thousands, of years before us, and undoubtedly to the countless wine lovers who will come after us. I’m just the tiniest speck in that crowd.

In the 1970s, of course, we could still enjoy grand crus Bordeaux and Burgundy for less than $25 a bottle, the greatest growths of Germany, Italy or Spain for less than $15, and rarities such as Chalone Pinot Noir, Stony Hill Chardonnay or Beaulieu Private Reserve for less than $12. I was fortunate for that, but less fortunate because we did not have nearly the staggering variety of wines from all around the world that wine lovers can choose from today. And of course, the average quality of wines today are at least ten times better than just 40, 50 years ago. As I said in the beginning, people today are so damned spoiled, and most of them don’t know it.

But I’m making this point because 40, 50 years ago all the best wines were judged differently, They used to be defined primarily by their origins. We clearly knew, starting at the top, that Latour was different from Lafite and Lafite was different from Mouton and Margaux because they all were grown in different places. It would be stupid to say Latour was “better” than Lafite, or that Lafite was superior to Mouton or Margaux; and pretty much the same went for all the grand and premier crus of France, or the individual einzallagen of Germany (it was in Germany, during the late ‘80s, where I got the most firsthand experience of terroir as a sensory, rather than just a theoretical or intellectual, concept).

We clearly understood, even back then, that wines of California, or Oregon and Washington, were a different matter altogether because vineyards and regions were NOT established, but more like stabs in the dark. Therefore, at the start of the modern era, domestic wines were evaluated, or compared, in terms of varietal identity and brand styles. How could we appreciate American wines as “growths” when the American wine industry still had little inkling of how grapes were grown, let alone where to grow them or how they were supposed to end up tasting once made into wines?

The first time I interviewed Andre Tchelistcheff for my local newspaper was in 1981, and I asked him when he thought California might produce wines from Pinot noir equal to those of Burgundy in France. He told me it will take a minimum of another 50 years—that’s how far behind the great Tchelistcheff thought America was compared to France in terms of raw experience and practical knowledge. I think the idea of more than a handful of American wines sourced from vineyards capable of expressing a genuine sense of place seemed almost insurmountable to him at that time. But honestly, I think Andre underestimated the will and wherewithal of American entrepreneurs with a yen for fine wine production. By the end of the 1990s, there were already well more than a handful of growers and vintners crafting wines, from Pinot noir and several other grapes, with genuine vineyard or appellation-related distinctions, even if it was accidentally rather than on purpose. Wines comparable, in their own bumbling “American" way, to the high standards long associated with the old European wine regions.

Today, there are so many more American wines that can now be considered equal to European wines if judged on the basis of the classic or traditional standards—that is, on whether or not they fulfill some kind of sense of place. But really, it’s probably only been within the past 10 or so years that we’ve seen something of a discernible mass of such vintners, finally brave enough to break away from the idea that wines need to be engineered to meet arbitrary varietal expectations, or earn some kind of reasonable score in order to be deemed worthy of attention or prestige. Today there are probably countless American vintners who don’t give a damn about scores and are doing just fine making wines to meet their own sensory objectives and selling them out, primarily to their own loyal bands of followers.

American vintners are growing up—fast, probably faster than what Tchelistcheff expected—and the consumer is finally benefiting by having access to a greater variety of homegrown wines sold on the basis of distinctive attributes, not because they’re meant to “better” than other wines. More wines deliberately made to reflect tastes of grapes shaped by origins, and appreciated for that. This has also been inevitable because of the simple fact that now there are so *many” American wine regions, and therefore demonstration of localized distinctions—rather than a varietal character that is supposed to hold true for all regions, or levels of intensity measured by numerical scores also applicable across regions—has become more of a priority for American vintners, especially those competing in conscious awareness of differences inherent in their respective regions.

That is to say, more and more Sta. Rita Hills Pinot Noir specialists are no longer worrying about making wines that meet the standards of those of Russian River Valley, or else Santa Lucia Highlands, Santa Cruz Mountains, Anderson Valley, Dundee or McMinnville. Not everyone in the trade and media has caught on to this somewhat subtle shift in mental approach, but many of the best growers and producers are now more concerned with capturing their own respective typicities and measuring their success accordingly. About time!

Example #2: When I moved to my current home in Lodi in 2010, one of the first things I did was organize a project called "Lodi Native,” in which I prevailed upon local Zinfandel specialists to throw out their personal or brand styles, as well as any commercial conceptions of the varietal, and produce minimal intervention bottlings under a banner meant to solely highlight attributes of chosen old vine plantings (plenty to choose from in Lodi).

In the beginning, some of the Lodi Native participants had to be dragged in kicking and screaming, but a bunch of them came around, and subsequent bottlings were not only a big hit among their followers, media as well as some of the trade (the trade can be slow about these things), but the project also had a big impact on many of the other wines (not just Zinfandel) produced in the region. Even though the project was about vineyards, not the varietal, writers like Alder Yarrow went so far as to say Lodi Native helped to restore his “faith in the future of California wine” (re https://www.vinography.com/2015/09/the_zinfandel_revolution_conti). On a broader level, it helped better define Lodi as a winegrowing region, which is crucial when you are an appellation trying to carve out a tangible identity. On top of that, the Lodi Native project has since attracted a slew of more independent vintners based outside the region; artisanal style producers, many of them “cool kid” independents, suddenly appreciative of the unique vineyards and grapes grown in the region. Shifting focus on terroir and away from “better than thou” wine production works!

As you might imagine, being able to be part of something like this, while extending my career long enough to see this ongoing evolution for myself, definitely floats my boat. This is also why—I’m sure you’ve noted, Tom—I’ve been a dogged proponent of natural styles of American wines. What do you expect out of someone who used to sell Domaine Tempier in the early ‘80s, when every bottle was still an “adventure,” and most Americans still didn’t know what Chardonnay was?

Many (certainly not all) of these new-fangled, handcrafted American wines, accumulating in an ever-increasing wave, might indeed be flawed in one way or another; but the way I look at it, Rome wasn’t built in a day. On the other hand, these are also the wines that stand the greatest chance of meeting the standards set so long ago by, say, French grand or premier crus. The less you do to a wine, the higher percentage chance of capturing typicity, terroir, authenticity, whatever you want to call it. Don’t blame this “new generation” of American vintners—it’s those damned Europeans and their quaint, age-old ways.

Still, I think it's funny when I hear people knocking things like Biodynamic farming, or anything smacking of minimal intervention winemaking, when these are the very practices that have always distinguished the greatest wines of France from DRC, Beaucastel, and Marcel Deiss on down. Sure, many of these muckety muck French wines are not exactly “clean” either, but their objective has always been to taste exactly like where they are grown or what they’re made from—precisely the reason we consider them “great”… the “classics!"

That, in so many words, is why I love wine. No long, laborious thought process ever proceeds along a straight and narrow line. It *should* be a little crooked or messy. When you break barriers, you’re not supposed to know exactly where you’re going to land. But it’s exciting. I think a lot of people on the conventional side of the industry still have a hard time with this. Meanwhile, though, consumers are responding anyway. Try stopping, for one thing, this so-called “natural” movement. It just keeps growing no matter what anyone says, mostly because many wine lovers are waking up, just like I did over 45 years ago, and realizing that wines made to be true to their grapes, with a sense of place unlike any others, are far more interesting than wines that are made to be clean, predictable, universal… and boring as hell.

TOM: Thank you, Randy. You’ve been generous.

👍

Every time I read a Fermentation entry I think to myself, “So glad I subscribed.” But this absolutely is the best so far. I think I learned more about winemaking, the wine business, terroir, and wine writing in this 5-10 minute read than I have in a very long time. I give this Ramble, and Fermentation “100 points.”

😈😂😂😂😂😂😂